This document contains an open letter, also published as a Commentary in the inaugural issue of CABI One Health, followed by a list of authors and other signatories (I am not an author of this text, but did sign it). Researchers and other experts in relevant fields are welcome to add your signature via this form. The list below will be periodically updated to reflect new signatures. If you have questions, comments, or media inquiries about this open letter, you can write to animalsandSDGs@gmail.com.

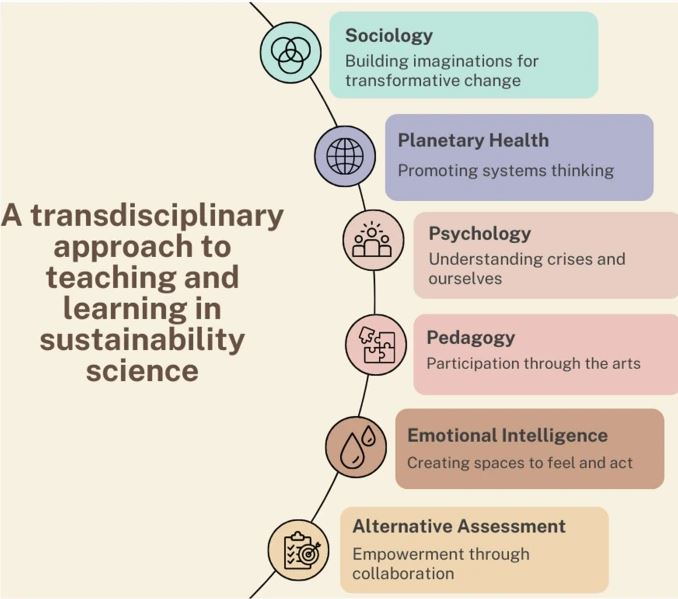

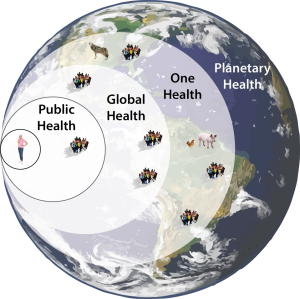

Animals matter for sustainable development, and sustainable development matters for animals. As the One Health framework reminds us, human, non-human, and environmental health are linked (Zinsstag, 2020), and many experts agree that every Sustainable Development Goal interacts with animals in some way (e.g. Keeling et al., 2019).

Yet animal welfare – that is, the mental and physical state of animals – remains neglected in sustainable development governance – that is, the goals and policies that governments are pursuing to promote sustainable development. For example, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development comprises 17 goals and 169 targets on topics ranging from hunger and poverty to peace and justice (United Nations, 2015). But while several of these targets focus on conservation of biodiversity, species, and habitats, none references animal welfare.

In June 2022, governments will convene for the UN Stockholm+50 Conference, which marks 50 years of international decision making on environmental issues. At this conference, governments have an opportunity to recognize the intrinsic value of animal welfare and the links between animal welfare and sustainable development, and to aspire to harm animals less and benefit them more as part of sustainable development governance. We call on governments to take these steps for the sake of human and non-human animals alike.

Animals matter for sustainable development. While its origins remain uncertain, COVID-19 has reminded us that industries like industrial animal agriculture and the wildlife trade not only harm and kill many animals per year but also contribute to global health and environmental threats that imperil us all (Roe et al., 2020).

For example, industrial animal agriculture keeps domesticated animals in cramped conditions and administers antibiotics to stimulate growth and suppress disease, contributing to infectious disease emergence and antibiotic resistance (Silbergeld et al., 2008; Roe et al., 2020). Animal agriculture is also a leading contributor to climate change, and it generally consumes much more land and water and produces much more waste and pollution than plant-based alternatives (Poore and Nemecek, 2018).

Similarly, the wildlife trade often keeps non-domesticated animals in high densities, either by capturing them from the wild or by raising them in captivity. This practice again contributes to infectious disease emergence (Karesh et al., 2005). Many methods of capturing animals also damage the environment; for instance, industrial fishing contributes to biodiversity loss, seabed damage, and plastic pollution in aquatic ecosystems, among other harms (Pusceddu et al., 2014; Thushari and Senevirathna, 2020).

Sustainable development matters for animals. Scientists increasingly accept that many animals are sentient (e.g. Low et al., 2012; Birch et al., 2021), and ethicists increasingly accept that sentient beings matter for their own sakes (e.g. Regan, 1995; Singer, 1995). It follows that humans should consider the interests of many animals when deciding how to treat them.

The stakes for animals in international environmental policy are high. Industrial animal agriculture and the wildlife trade not only harm and kill hundreds of billions of non-humans per year directly. They also harm and kill countless non-humans indirectly, by increasing disease outbreaks like bird flu and COVID-19, extreme weather events like fires and floods, and social and economic disruptions like lockdowns and supply-chain breakdowns that increase the risk of human violence and neglect towards non-humans.

More generally, environmental changes like climate change, ocean acidification, and air, water, and land pollution are not only reducing biodiversity but also harming and killing countless animals by making it impossible for them to breathe, eat, drink, or otherwise survive. Some mitigation and adaptation strategies – ranging from the intensification of meat production systems to the construction of cities and transportation systems without appropriate safeguards – risk harming and killing animals unnecessarily as well.

These links between human, non-human, and environmental health all matter for sustainable development governance. Humans have a responsibility to consider the interests of everyone impacted by human activity. In particular, humans should harm animals less and benefit them more as part of sustainable development governance, for instance by reducing exploitation of animals as part of pandemic and climate change mitigation efforts and by increasing assistance for animals as part of adaptation efforts (Sebo, 2022).

Fortunately, governments are making progress. For example, in 2020, several UN bodies established the One Health High Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP) to provide guidance on ‘issues raised by the interface of human, animal and ecosystem health’ (FAO et al., 2021). And in 2022, Environment Ministers at the fifth UN Environment Assembly requested the UN Environment Programme to produce a report to improve our understanding of the nexus between animal welfare, the environment, and sustainable development (UNEA, 2022).

Fifty years after the adoption of the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, governments have the opportunity to build on this progress. They can:

- Recognize the intrinsic value of animal welfare and the relationship between animal welfare and sustainable development in Stockholm+50 outcome documents and subsequent international sustainable development outcome documents.

- Strengthen and broaden the One Health activities of the OHHLEP and other relevant entities to better reflect the value of improving animal health and welfare not only for the sake of humans but also for the sake of the animals themselves, as well as consider animal health and welfare in the impact assessments that shape policy decisions.

- Support policies that benefit humans and non-humans alike, including informational policies that educate the public about human, animal, and environmental health and well-being; financial and regulatory policies that incentivize co-beneficial practices; and just transition policies that support vulnerable populations.

We call on governments to start including animal welfare in sustainable development governance now, towards a healthier, more resilient, and more sustainable world for all.